Dusty blue berries

Pine-sweet on autumn branches

Gin dreams in waiting

Let’s begin at the beginning. The magic juniper berry.

Junipers are conifers. The trees are beautiful, and can live an incredibly long time, easily over 1000 years.

Juniper tree’s name is derived from the Latin word juniperus, which in turn is a combination of the word junio, which means young, and parere, to produce, hence ‘youth producing’, or evergreen.

The traditional drink jenever and its French take genièvre are both words for juniper. The French name was eventually shortened to geneva, sounding the same as the place name. This is worth noting, as we will return to a discussion about Madame Geneva later on. This name, Geneva, was later on further abbreviated to ‘gin’, presumably by people that found three syllables exhausting.

The name ‘gin’ then, is defined by its signature botanical. Gin is juniper. Handy, and makes one wonder how the world might look if everything you eat and drink was named after what it tasted like. It’s bizarrely rare, and the only other example I could come up with after five minutes of thinking about it was mint.

The word Juniper itself came to be a common first name for girls, and has continued to evolve over time. Juniper as a name is still well used now - it was in the Top 1000 names in the US last year. It is also the root of other names like Guinevere, Jennifer, my mother’s name, and Genevieve, my stepmother’s name (a pattern emerges).

The berries themselves are a spice. If you’re feeling brave, bite one. Whether you like gin or not, it’s an extremely well known flavour. These berries - they are actually cones - balance a resinous, balsamic warmth, with a fresh, citrus clarity. It’s an ancient flavour, and it has been part of the human diet since the end of the last ice age. As the glaciers retreated, the first greenery to grow were conifers, and juniper was, and is, one of the most successful ones.

As we became farmers and cleared woodland and forests to create space, juniper thrived. Archaeological evidence shows that juniper found its way into the diets of people everywhere - in Europe it was most common in Scandinavia, Germany, and the Low Countries, but juniper species are common across Asia and North America.

That flavour - if you can still taste it after you bit one a couple of paragraphs ago - is a timeless taste that connects us all the way back, as far as we can go as people. The horticulturists tell us that the berries themselves are unchanged in 15,000 years since the last ice age, and all the way through that time people have used that balm and that citrus to cut through the richness of dark meats and game. Today it will still be prominent in the marinade for venison or rabbit or duck, just as we know it was in the communal cooking pot thousands of years ago.

Juniper was never just for cooking though.

Putting flavouring for stews to one side, in almost every culture there is some role for juniper as a sacred symbol, or as a healing power, or for use in some kind of magic. In Syrian tradition, juniper was the manifestation of Asherah, the wife of God/Yahweh, and it is a recurring theme throughout the Old Testament, where it is always a sign of protection and fruitfulness. King Solomon built his first temple from juniper, Joseph, Mary and Jesus hide under a juniper tree from King Herod, and so on. Further afield, in most of the cultures in which shamanism is found, juniper is the primary incense of the shamans.

Juniper was part of the embalming process in Ancient Egypt and was a standard treatment for a large number of different ailments across the whole Roman Empire, where they would burn juniper, or rub it in, or eat it, depending on what was going on at the time.

There are many, many Neopagan practices like burning juniper twigs to purify a building or hanging a bag of berries around the neck of a baby to ensure a lifetime of good health, and so on. When the Black Death took hold, and the beak guys showed up all across Europe, it was roses and juniper that they stuffed their beaks with.

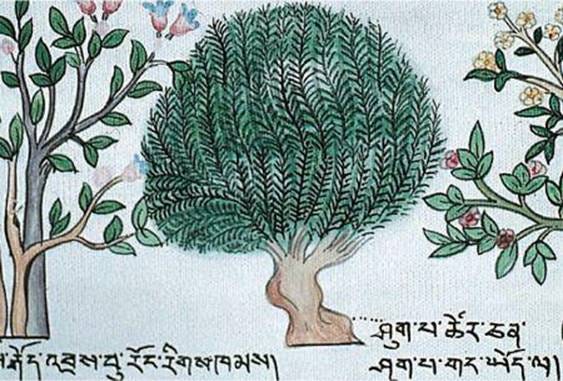

Traditional representation of a high mountain species of Juniper on a Tibetan medical thangka (painting).

Today, juniper is sacred in the Himalayas, amongst many other places. Branches of the plant are attached to the ends of the masts holding prayer flags. Sherpas in the mountains use the branches as amulets to protect them from falling or being hit by rocks. The branches are offered to the mountain spirits at the piles of stones typically found at passes.

In short then, we have spent thousands of years as a global society with juniper as a very central part of a lot of the things that we did that we felt were important. As western science has gradually eaten away at the edges of what we have always used traditional ideas for, juniper has today started to fade from our consciousness.

In the UK, it’s last over the counter use outside of the spice section at the supermarket is flea collars for cats, and you can still buy those stuffed collars now. I’ve been in other countries in Europe and seen juniper oil for sale, which is apparently for dressing wounds, or menstrual pain, or UTIs, depending on who you ask. Regardless, it is undoubtedly a strong antiseptic and an effective insect repellent.

People that don’t like gin will tell you that medicinal flavour is exactly what they don’t like. Most people probably only sense that flavour unconsciously, and wouldn’t recognise it as juniper without it being pointed out. Whether you are a fan or not, when a teaspoon of gin is sitting on your tongue, the first thing you notice is a clean, antiseptic burn. Then comes the defining note of juniper. It's reminiscent of crushed evergreen needles but with an almost citrusy, medicinal clarity.

It’s a flavour that humans have tasted for thousands of years and sits deep in our shared understanding. It seems likely that the last place it will live, in the west at least, is where it is now - defining a martini or fighting with the quinine in a gin and tonic or cutting through a venison casserole. It’s had quite the journey, and this feels far from the worst place it could end up.

So, hopefully we can agree that juniper is a central part of the human experience, that has run through our whole history. A taste of gin then, is like a time tunnel, whether we realise it or not. How do we get that taste? What about distilling? See you in Chapter 3.